To practicing attorneys, the pandemic seemed to change the legal system overnight. These changes, along with preexisting systemic issues, underlie the mental-health crises that affect attorneys throughout the profession—depression, anxiety, burnout, and substance abuse. Attorneys need to acknowledge and understand those conditions, as well as how to address them properly. This episode features Katie Rose Guest Pryal, an author, educator, and attorney who researches and writes on disability and mental-health issues, focusing on public discourse, mental illness, and neurodiversity. Being neurodiverse herself, Katie strives to make the world more accessible through her scholarship and teaching. She discusses the challenges of addressing mental health and how to cope with burnout in our ever-changing world.

Our guest is Katie Pryal. She is a law professor, an author, and many other things that we are going to talk about. She’s also my cousin. She’s the person in the law that I have known the longest. I have known her my entire life. Katie, thank you so much for coming on.

Thank you for inviting me.

We are glad to have you here. I know some of our readers probably know who you are through Twitter but those that don’t, will you tell us a little bit about yourself and your background?

I am a lawyer, an author, a keynote speaker, a law professor, adjunct now at the University of North Carolina School of Law.

You were an academic as well outside of law.

I was full-time at UNC Law for several years and stepped back to write full-time in 2014, but I still teach there as an adjunct and enjoy it very much.

You’ve got a graduate degree in Creative Writing, went to law school, and got a PhD in Rhetoric. You have not practiced. You have done the academic side of things. Is that a fair way to put it?

I have practiced in the margins. In fact, I’m an Attorney of Counsel at Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani, which is a known national firm. I average one matter a month with them now. Sometimes it’s more, but it’s a blast to work with them. I maintain my license and practice law. When I was getting my PhD, I practiced part-time at a workers’ comp firm that helped me graduate without debt, which is a nice thing.

Even though we get fellowships, we go into doctoral programs. I had a teaching assistantship. I had roommates, and we all squatted in a house together. It doesn’t cover everything you need, and we take out loans. I was able to work part-time with a flexible schedule for a workers’ compensation firm. I have practiced law in the margins and maintained my license. I have a firm of my own, mostly to help my friends get out of trouble.

You also did a Federal clerkship, and we could talk about it as much as you want. Yours had a unique aspect that I would love for you to share. We talked about it before.

I clerked for a Chief District Judge in the Eastern District of North Carolina at the time. I was thrilled because it was such a wonderful clerkship, but the location was special. It’s Elizabeth City, North Carolina, which sits on the Pasquotank River. It opens right into one of the sounds on the Outer Banks. I was on the inner inside coastline with the Outer Banks outside. I could cross a bridge and be right near Corolla, Duck, or Kitty Hawk if you know where that is.

I got to live out there, which was a lot of fun. There were a variety of interesting things that we got to do because we were in the Eastern District. Our jurisdiction included all the parks and national seashore. We had cases that were hilarious and also weird because of the national seashore. One involved the wild ponies and sea turtles.

We had some vacancies on the court. We would go and sit in New Bern, down the coast. We had chambers in Raleigh. We would travel some, and on one of our trips, he was like, “Let’s go to the lighthouses.” The public is allowed to go up the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse but they are not allowed to go up the others.

We’ve got to go up the one on Ocracoke Island, which I don’t recommend because it is very narrow. In fact, I got claustrophobic and freaked out in that one because I don’t know if a human nowadays is supposed to be able to fit inside that lighthouse. I am 6 feet tall and went up in that. As you go, it gets smaller. The stairs were so narrow, and I was ducking down to try to turn my body to fit these spiral stairs that were not welded together anymore.

It’s not very tall. The Hatteras is enormous. I was like, “I don’t feel a need to go all the way to the top of this lighthouse.” I came back down. This is on Ocracoke, and that’s the one where Blackbeard had his hideout. Ocracoke is an island. You have to take a ferry to get there. We ferried over to Ocracoke, and there’s the one in the Outer Banks that’s with the diamonds on it. I’m like, “This is Bodie Island, Hatteras, Ocracoke, and the other one.” I cannot remember what it’s called.

We have to go up that one, which is lovely, not scary, and Hatteras, which is extremely tall. I am a fit person yet not fit enough to get all of this. I was like, “I’m dying.” That was neat. This is on Federal land. The park rangers, who all knew my judge, liked and respected him a lot, escorted us into this Federal land. They let us see that. That was a real treat and was nice. We’ve got to see the ponies, which was awesome.

You think about a Federal clerkship, and being on the Outer Banks and all the wild animals is not something you think about.

I’m curious about your practice area and teaching concentration, both as a lawyer and law professor. What are you talking about and practicing?

I did work in Compensation Law before and all through grad school. I’ve got my PhD in Rhetoric, and that took approximately 3 and a half to 4 years to do that. During that time, I practiced law. When I was first brought to Gordon & Rees, it was to do workers’ comp but I branched out. They are like, “You can do Employment Law?” I said, “Yeah.”

I haven’t had a workers’ comp case since that first one. I do Employment Law, mostly contracts, non-disclosure, non-compete agreements, and things like that but that was not my area of research as a professor. My area of research was Disability Law. If you look at my publications on my CV, which you know is boring but if you chose to do that because you needed to fight insomnia, you could see my publications. They focus on mostly psychiatric disability, mental illness, any neuro divergence like that. It was my main focus. Disability studies is the area. That’s where I published the most.

My other major area of research was legal writing. It continues to be. I have a new article coming out. I placed it when it’s coming out in the next book of the Barry Law Review. I give a talk every other year. It’s the Biennial Conference of the Legal Writing Institute, which is the scholarly body of legal writing studies. I’m looking forward to that.

I keep my hand in academia in that way. Those are my two main areas, disability studies and legal writing. Hilariously, sometimes I’m an expert in legal writing issues. I will write an affidavit or a declaration for something in litigation. People find me, and they are like, “Does this comma mean what you think it means? These parentheses don’t change the meaning of this sentence.” I have done that all over the country.

I have never heard of this. You get to do that. People hire you to pick apart their writing.

Mostly it’s dumb stuff. Somebody is trying desperately to win their argument and do it on something very specious. Yet someone else is like, “I still need to submit something. Can you please say that this is dumb?” I’m like, “I can’t say it like that but I can say it in a way that gets to the point.” I’m a grammar expert.

One of the things you have published is The Complete Legal Writer series with Alexa Chew. We don’t have to talk too much about it but I love it because it introduces the idea of teaching through genres. If you want to talk about that a little bit, that’s a cool approach.

The new article is called Genre Discovery 2.0, which is coming out in 2022. It’s an editorial. The first article was The Genre Discovery Approach: Preparing Law Students To Write Any Legal Document. It’s a big, bold claim, which is how we should title things. I wrote this article back several years ago. That’s why the new one is coming out. It was 2012 or 2013.

This is my Ph.D. in Rhetoric and Composition. It’s the idea of using genres to teach legal writing. What that means is you don’t teach people to write a particular office memo or appellate brief. You teach them that appellate briefs are a genre, which means a document type that exists beyond the one that they are writing and will exist after. It’s a recurring document type.

If it recurs, that means it has conventions that we follow when we write them. That’s how we know how to identify them. If you put 4 appellate briefs and 1 office memo, you could pick out which one was not the appellate brief. The reason why we are able to do that is that genres exist. “Which one is the office memo? That one, because it’s not an appellate brief, these are.”

That doesn’t mean that all appellate briefs are exactly the same. It means that they share conventions, which are not rules or templates. They are conventions. If you can learn the conventions, you can write an appellate brief in different situations. This jurisdiction has different rules. That’s fine. You can learn those rules and conventions because you know how to learn them.

What we teach in The Complete Legal Writer, what I suggested in this original article, and what Alexa helped me transform into something teachable is how to teach the student to teach themselves the genres they have never encountered before. When they go into a summer internship or practice and someone says, “You need to write a bankruptcy brief,” and they are like, “I didn’t learn that in law school.” That’s fine.

You go and get five samples out of your firm’s files, lay them out in front of you, and study the conventions. There are similarities. What do they have in common? You can figure out the conventions if you have the skill of discovering a genre. No genre is undiscoverable to you. You can discover anything. The idea is empowering students to teach themselves.

I love it because it’s something that all of us have done at some point. You are at a firm, you get on the system and search for whatever it is. It formalizes and gives it a name rather than looking around on the system blindly.

We already use go-bys. Instead of hacking it together, I said, “We use go-bys. We do this.” What do we do exactly? Let me analyze this and put it into practical terms. Find some samples, sit down, look for these things and take this. That’s the thing that we teach ourselves to fumble through in our first year or two of practice. Now the students enter practice and are already able to do this. They are like, “I need some go-bys, and we are going to have three. Thank you.” Ideally, even in front of the same judge. They come and know what to ask and look for. This is a real skill.

I love that label because it accurately describes what we do when trying to teach ourselves. Even as lawyers, you get new assignments. You run into an area that you are not familiar with necessarily, and in many years of practice, you are still looking for a form, a template or a go-by. I like that name of framing it into the genres. It’s cool.

The Complete Legal Writer is the first book in a series. Jody might know this already. It’s called The Complete Series for Legal Writers. The Genre Discovery is pulled through all of the books. The second one is The Complete Bar Writer, which is focused on the MPT, the Multistate Performance Test. I’m not sure if it wasn’t part of the test when I took it. That’s the one where students are given a case file and have to write some genre.

We wrote this book with the idea of genre discovery. What if you are given something and don’t know what it is? How do you discover what the genre is and how to write it? We brought it through to that book. The third book is coming out in the spring of 2022. It’s The Complete Pre-Law Writer, which is targeted towards students entering law school, in summer programs, undergrads but also paralegals, and others who are lawyer adjacent. It’s a condensed version with assignments instead of a higher litigation process. In The Complete Legal Writer, it’s six writing assignments. The genre discovery thing is the thread that connects the whole complete series.

Another thing that you do is fiction writing and publishing. If you think about the technical requirements of legal writing it seems a world away, but are they different or can they influence each other in a good way?

I write law textbooks and trade nonfiction, which is trade books, as opposed to academic books. I also write novels. I view them on the spectrum of the novels way over here on the one side, the textbooks on the other side of the spectrum, and the trade nonfiction in the middle. There are footnotes in those. They are in the middle. I went about that all wrong and put them all on a list by year. It made this table where I was like, “Katie, what have you published every year since you started writing books and how they are grouped together?” It’s like, “What have I written and when?”

It was a very enlightening experience because I found that I do a novel, a textbook, and then a trade nonfiction book. There’s a reason that my brain wants to spread it around like that. Everybody is different. They are different types of writing, and I enjoy them all. They each feed my soul and allow me to share my thoughts with the world in a different way.

I want to do them all at the same time, which is my job. I feel very lucky. I don’t know about your practice areas but doing the exact same thing every day would be boring. I feel that way. If you look at each year, it’s like a textbook, and there was a novel, there’s maybe trade nonfiction and a textbook. It’s like that. I didn’t think about it. It’s how the work came around.

Are there conventions and ideas from writing fiction that adapt particularly well to legal writing?

The first thing that I learned about writing any sustained piece of work was from a friend of mine, who’s a novelist, right after I finished my Master’s in Creative Writing. He said, “Books are about structure. Short stories and poetry, whatever. I don’t know about this but when you write a book, it’s about structure. Everything else follows from there.”

I don’t know if everybody would agree with him but it made perfect sense to me. When I sit down to plan any book that I write, I start with the structure. You can think about the architecture. What is the architecture of this novel, law review article or appellate brief that I might write? I wrote a trial brief. You start with this big picture view of the main arguments and like, “Where does the law fall?” It’s structure.

I don’t write strict outlines of my novels. That’s not what I’m saying. I’m saying there has to be a beginning, some end that you are aiming towards, and a structure as you go. The things that have to happen for the story to hold together. Otherwise, you have a meandering mess but that goes for everything you write. You don’t turn that into a judge. You don’t want to your textbook to be a meandering mess. My novels are tight, and the best ones are. They are fine-tuned as far as structure goes.

It wasn’t COVID-19, so my memory worked, but either John Updike or Mark Twain said that the ending of a story should be unexpected, surprising and expected. In other words, you have to set it up in such a way that it’s not predictable but also the most obvious way it had to go, which is an extremely difficult tightrope to walk if you think about it.

One of the things that is interesting about your career is that you made the decision to go freelance both in terms of your publishing and academia. How did you make that decision? Even in the old strictures of legal practice, there are a lot of people who would love to find a way out of those barriers.

I have meant to be very honest about money when it comes to being a writer because a lot of it is shrouded in secrecy, and I don’t like that at all. I was able to leave academia full-time because one of my textbooks started making enough money for me to do so, and I have a spouse who has healthcare. I was employed by UNC, and we were on my medical plan, which is the State Health Plan but we were able to join my husband’s health plan. The income from one of my books took off. I was able to leave higher education and concentrate on writing full-time. You could consider that luck. I did work very hard. I wrote 3 books in 3 years. This was when I had 2 kids in less than 2 years and wrote 3 books in that span of time.

My kids were born in ‘09 and ’11. My first book came out in ‘10, and then ‘11 was the next book. The next one came out in January ’14 but that was it. I was able to leave in ‘14. I feel very lucky that I had this. It’s like the Pareto Principle, the 80/20 Rule. Eighty percent of my income is this one title, 20% of my providing income, and 20% are all my other books. If you ask authors who make a living from their books, that’s the way it is. You have one book that hits, and then you write and write. Maybe in another several years, you will have another one. It’s how it is. The rest of it is work a day, grinding out, except I love it. So I’m not actually complaining about the grind.

One of the other things that I wanted to talk about that threads a lot of this stuff is a discussion of mental health and disability. It’s something that you are very outspoken about. It’s something that you know more about than anyone I know and how it plays into both law and academia because I don’t think they are very different approaches.

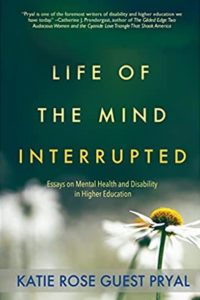

My second bestselling book is on mental health and higher education, Life of the Mind Interrupted: Essays on Mental Health and Disability in Higher Education. That one came out in 2017 and is selling more now than it did when it first came out, which is probably a sign of the times. I have another one I finished with a press at the moment. Fingers crossed that it passes review and it’s Darkness Interrupted. It’s a sequel and is very much a book of the now but it is also about mental health and crisis situations.

I went to law school and started in 2000. My second year was 9/11. We had psychologists who studied these things. We had a population shock event occur, and the aftermath of that was the change in how we travel, the TSA, Homeland Security, all these big changes in our society, the war on terror, and the terror alert colors. It was many years ago. If you think about it, we were all a little on edge.

If you lived in the New York area, you were on edge a lot. I went to visit a friend of mine, and he said every time a siren went off for years, he would jump out of bed and freak out. He couldn’t help it. He didn’t work downtown. It didn’t matter. It was a citywide post-traumatic situation, and that’s normal. We are living in this extended worldwide population shock event. This book is about population shocks, including COVID-19. It is also a book on higher education.

The content is about how to deal with this, how it affects burnout, and how it affects your day-to-day life. It extends way past higher education. It happens to be my very special area of expertise. The subtitle is Reckoning with Mental Health and Higher Education now. It causes us to have a reckoning with mental health in a new way. People who might not have spoken about mental health before COVID-19 are willing to talk about it now, which is a good thing, even though I wish people were not suffering. I’m glad that we are able to have these conversations.

It’s such a pervasive problem in the law and always has been. It’s something that the law has been particularly slow to catch up to because, to your point, I have seen it come out a lot more in the last few years, probably more than the previous several years before that when I was a law student and a lawyer. You didn’t talk about it because there were worries about getting into law school, being able to take the bar, passing character and fitness, and all of those things, which discourage people both from seeking treatment and talking about it in ways that were particularly harmful, although maybe not intended to be that way.

I wrote a piece for Slate years ago. I don’t remember when it was. The title was The Worst Part of the Bar Exam, which was not a title I would have picked because we are lawyers, and we hedge the worst. That doesn’t get clicks. I co-authored it with another law professor. We talked about the character and fitness and mental health. It is an invisible barrier that no one knows about unless it affects them. It’s horrible because, at least in North Carolina, I had to do this. I filled it out, and I wouldn’t know if I passed the character and fitness until after I took the bar. They didn’t let us know.

You take the bar exam, do the best you can, and maybe you pass the actual test but it’s not. We have to wait until January filling this out. When I got to those questions, which I did not know were coming, it was another problem. We need to tell everybody. That needs to be a worldwide announcement in law school.

You are going to be asked these questions. We are going to help you with them. This person is an expert in this area and will help you with them. That wasn’t, of course, there. When I got to those questions, I just started sobbing. Do you have these diagnoses? If you do, sign this blanket release so we can get all your medical records. That was the deal. I was like, “I don’t want to do this.”

It felt super invasive, and it also made me feel like the members of my state bar did not want me to be a lawyer and welcome me into their ranks. What set me on a path of disability studies was that experience. I gave a talk about this very subject at George Washington about psychiatric disability, the legal profession, and gatekeeping.

I hold the character and fitness questions from various states and put them up there to see. There has been a movement to get rid of those questions. What I talked about was what this does is not protect the profession by any means because you are keeping out people who have sought treatment and are encouraging people not to seek treatment. They don’t have to answer yes.

Have you ever sought help from a mental health professional? You get to say no if you didn’t, and that’s not good. The statistics on law students and depression are depressing. We are at 40% now, by the time they graduate and then lawyers themselves. We are the most depressed group of people on the planet.

The second main group of people that I talk about mental health is lawyers. I give at least one talk a year to talk with lawyers about mental health. We are not doing well, and we have never been doing well. There are things that we could do better to fix that problem but it requires an institutional level will.

It dovetails into the giant numbers that relate to substance abuse in practicing attorneys very much so. I love that you apply the disability lens to it because I don’t think that’s necessarily an intuitive thing for lawyers to think about. Can you talk about disability and what falls under that umbrella? It might surprise people.

The term psychiatric disability is not something a lot of people have heard. When we think of disability, we think of wheelchairs. Psychiatric disability is what we might call mental illness but it can be broader than that. You can have a mental illness and not be mentally ill. I have bipolar disorder, I am autistic, and I am disabled. As I speak to you, I am a person with disabilities. I could apply for accommodations if I needed to at a job. That’s what disabled means. I can get more into life activities but I have disabilities that are recognized by Social Security Administration.

If you have suicidal depression or bad anxiety, and it is so bad that you can barely get out of bed, you have a mental illness. You might not have had that your whole life, and then one day you suddenly have developed major depression. It happens. This story I tell often is William Styron, who wrote the book Darkness Visible. I poached his title for my new book. It came out in 1990, and this is the author who wrote Sophie’s Choice. People know that because it was a movie and he wrote this book.

At the age of 60, suddenly, for the first time in his life, he was hammered by suicidal depression. He tells a very good story. It’s a short book. It’s 90 pages of what it felt like. It’s amazing that he could precisely describe it like, “This is what it was like. I couldn’t remember where my hotel room was because of this amnesia thing that could happen.” He had gotten an award. He couldn’t remember where to go. He is so depressed. He wanted to die. Up until he was 60, he did not have depression. After 60, he is a person who had depression until the day he died, and it didn’t go away. He became psychiatrically disabled at the age of 60.

It can come from nowhere or a situation that might happen. Someone might have postpartum depression. Depression becomes something that a person might battle forever. A huge population shock event might happen and create anxiety. Anxiety disorder diagnoses in this country are up 25%, according to The Lancet. This is a big deal.

Anxiety disorder is a psychiatric disability. People don’t like to think of themselves as disabled. That is not something that a lot of people want to identify with. I often say to people who identify as disabled, as I will say that when I talk about these things because the word disabled will make people go, “I don’t want to be that.” They might reject the idea of seeking help.

For other people, being able to identify as disabled brings them into a community of people who are also disabled. There’s a strong disability community. That’s another reason, too. There are benefits but I am careful when I use these terms and explain what they mean. That it’s okay if identifying as disabled is not something that you want to do. It’s important to recognize if you have an anxiety disorder, depression or feel like you are falling into burnout, which is not an official diagnosis. It’s something that psychologists recognize and can lead very quickly to other things that are more serious that you should seek treatment for those things.

You touched on burnout. I want to go there a little bit because I know it’s something you have talked about and written on a lot. It’s something that everyone has had a touch of in the last few years, whether it has been severe or not, particularly in the legal profession over the years. It has always been a problem but it has become exacerbated.

I gave a talk on burnout to a bunch of lawyers. It was nice to talk to lawyers about it because we struggle with burnout as a profession more than others do. One of the things I said was, “It’s a lot easier to recognize burnout among your employees and help them through that than it is to lose your employee and have to start all over again with a new one.” How can we prevent that from happening?

The talk itself was on what I call systemic burnout. The important thing to think about now is that because of the population shock we have experienced with COVID-19, the burnout is related to that, and it is systemic if a population shock is an unexpected negative event that disrupts a large population. It doesn’t have to be worldwide. We happen to be in this worldwide one, but it can be 9/11 or a school shooting in a town like in Parkland. That’s a population shock in a city.

These population shocks increase the prevalence of anxiety and depression. I’m arguing in my research that these population shocks lead to burnout but it’s a systemic burnout. If burnout is stress compounded over a prolonged period, and we have fallen suddenly over a prolonged burnout, then systemic burnout is widespread among a large population caused by these large-scale shock events. The hard part is that it’s difficult to spot systemic burnout because it is prevalent.

If everybody is walking around in a stupor, it seems like that stupor is normal. That’s what makes it hard to deal with and even identify systemic burnout when it’s happening. Everybody feels terrible. I’m not special. We are all in the same boat, all these things we say to ourselves to make ourselves feel like nothing is wrong. We are lying, tricking and gaslighting ourselves.

We are all in the same boat, and that boat is sinking. Around 40% of workers are identified as being burned out but only about 35% said they were doing anything about it. I’m like, “What are we going to do?” The problem is that the solution to systemic burnout is we keep putting the burden on the individual to fix it. “Do yoga, self-care,” and all of these things.

I’m like, “It’s a systemic problem. It needs large scale.” I want to distinguish it between institutional, which you could argue the legal profession has an institutional burnout problem. I also believe it’s true. That’s within an institution created by institutional culture. We have a double whammy happening. We have this systemic burnout with COVID-19. We have an institutional culture in the legal profession that also can lead to burnout, depending on your workplace, your supervisor, and the demands of your job. We can agree that as an institution, the legal profession has this burnout problem. We have all established that.

Burnout, although not a recognized diagnosis, leads to anxiety, depression, and people leaving their jobs. The main thing you see is this detachment, cynicism, and lack of caring. If you are still feeling stressed out, frazzled, and worried that you are not getting your work done, you are not burned out yet. You still care. “I missed a deadline. I’m upset.” It’s when you stop caring that you missed a deadline. When your inbox is full, you are like, “How am I going to answer all these?” You need to worry before that. You should head it off.

You are burned out if you are detached. You feel like, “Nothing I do matters.” It’s the, “Who cares? It doesn’t even matter that I’m here. I make no difference.” Those thoughts are burnout and a red alert. How do you prevent that? When you are feeling frazzled, stressed, overworked, nothing you can do can get you back to negative ten. You want to be at zero. You are in the red. You are never going to be in the black. This is how many of us feel. We are trying to catch up, stay afloat or pick a metaphor. That is when you intervene. You are going to say, “Katie, how do we intervene?” I have some answers.

There’s the employer and the employee side of things. They are different. We are all workers, and whether we are supervisors or not, we are looking for missed deadlines. We are spotting it. Systemic burnout and institutional burnout are harder to see. This is the double whammy that the legal profession faces. They missed deadlines but even more than usual. This person is always a little late but now they are really late or a person who never misses deadlines and now they are missing them. It’s the work or personal events that you keep forgetting. I can’t remember if this is Twain or Updike, and I can’t even remember the quote. It’s something I used to be able to recall. This is this COVID-19 like amnesia that’s happening.

I was supposed to turn in a major assignment and completely forgot about it. I did not miss the deadline. I was unaware. It fell out of my head completely. There is a regular Thursday social. I forgot it was Thursday and forgot the social. I didn’t go. That’s being overwhelmed and forgetting things, and then there is the didn’t want to attend the social. That’s the detachment.

You’ve got to pay attention to the difference here. Your email inbox is full, and you can’t get through it or you don’t want to get through it. Overwhelmed, detached, notice those things. If you are a supervisor and you have an employee who’s not responding quickly enough to your emails and opinion, maybe instead of getting angry, ask them how they are doing. That’s the thing.

If you are a person who is objectively not a failure but you feel like you are, you need to get help right away. For example, the three of us are objectively not failures. This idea that you feel like a failure can sometimes take one tiny thing going wrong. It’s the stupidest, smallest thing. I’m not talking about losing a big case.

Even losing a case, we get to do that. We get to lose sometimes, and we still are not failures. Sometimes the judge woke up on the wrong side of the bed or had a bad sandwich. That happens. You feel like nothing you do matters, and you are a failure. It’s a red alert. If you are a supervisor and you can see that someone who used to have that pep in their step doesn’t anymore, you need to ask.

On the worker’s part, it’s noticing that you are overwhelmed before you are burned out. If it’s too late, you are already burned out doing something about that, too. If you are a supervisor, you need to look towards the cause and not towards the individual. It’s very rare with burnout that a person’s individual actions caused it, especially nowadays. This is a social problem. It’s systemic, so it requires structural solutions, for example, workplace solutions. We are in the legal profession, which already has structural problems. Here we go like, “What can we do?”

The first thing is that we need to lower our workplace expectations. This is hard because we are all finally getting back to work. The opposite thing is happening. What should be happening is that all those cases and calendars that got backlogged at court, instead of lowering expectations, they are getting higher. That’s the reverse of what needs to be happening now because we are already at the end of our ropes.

People who have the power to do this need to figure out a way to lower expectations, and that requires recognizing we are nowhere back to normal. Even if we go into the office, put on our suits, sit around and look at each other face-to-face, we are not back to normal yet. The other thing is to check in. Don’t wait until they keep missing emails. Make these burnout check-ins safe and normal to happen. You can call them whatever you want.

You have to earn the trust of your employees for this to work. You’ve got to do it a lot. The first time they are going to say, “Everything is fine.” What else would they say? We are all scared but maybe by the fourth time you ask, they might start to answer honestly, “I feel like if I have to work this weekend, I’m going to fall to pieces.” It is what you need to hear.

You need someone to tell you that truth. You do not want your employee to fall to pieces because you have real trouble. That’s where the missed deadlines, filing deadlines, and things like that. To that point, I would suggest you put safeties in place, especially in law firms where things like missed deadlines can matter. This mental load we are carrying is so high that failures are going to occur. They are bound to happen. Balls will get dropped. Prevent them.

Put people in teams and have people review other people’s work. I do this myself. There is another employment lawyer in my office here. I went through something that seemed obvious in his contract but I called him on the phone in one billable minute. I said, “I want to double-check this with you. Make sure I didn’t miss something dumb.” That’s where we are now. We have this heavy load on our brains. Half of our brains are given over to, “Did I send my kid with a mask?” We don’t have that brain space to think about everything we used to think about. We need these safeties.

You can pair people up on projects that we used to do individually. They can have the same number of projects. They do them together and catch each other. This is a very basic suggestion. Whatever the safeties might be, put them in place, have someone double-check, expect the failures to occur, and be okay with that. I know it’s hard to accept the fact that that’s the reality you are in but it is.

For workers, asking for what you need is important. How to do that will be harder. What I have found through my research is that the more specific you are, the better. Instead of saying, “This job is burning me out.” That’s not good. Don’t do that because what your supervisor is going to hear is, “I hate my job.” That is most likely not the case. You wouldn’t be talking to them if you hated your job. You would have quit.

What you are going to them for is help. “I have worked every weekend this month. I feel like I’m at the end of my rope. Can I please have this weekend off to catch up and catch my breath?” Be very specific with your ask. “This project is causing me some problems. Can I switch places with this person or take on a different project and hand this one off to someone else?”

The more specific the ask, the better. Another thing to keep in mind, if you are a worker talking to a supervisor is that your supervisor is also drowning. Simply because they are your supervisor, it doesn’t mean they are doing great. They are also having a hard time. You need to be sympathetic to them as much as you want them to be sympathetic to you.

Lastly, if you are the supervisor, you can open up a bit and lead from the front by sharing that you are also feeling the pressure and say, “I know how you feel. I also worked the last four weekends.” Not in a way to say, “I worked the last four weekends. Why can’t you?” That’s terrible. Don’t do that but say, “I have worked a lot of weekends, too. I understand how hard that can be and also feel this pressure. I’m so sorry that you feel this way and take the weekend off.” If you open up, reveal your own suffering to your employee and create that bond, they are going to come back and share with you when they are in trouble because you lead them from the front. That’s all I’ve got on that.

We have talked before here on our show about the pressure in the legal profession to appear bulletproof and the culture of our profession. You can use the word toxic, I suppose. It’s not overstating it. Jody and I had the pleasure of starting this whole project during the pandemic. Over the course of the last few years almost, we have seen some change.

People are more willing to talk about mental health issues, stress, self-care, and all that. It’s good to have some practical advice on not only what the employer can do in the situation. I know you said that so much of it gets shoved down to the individual but it starts on the individual level. You have to have that realization of, “I’m not okay.”

There is something that the individual can do. You make the point that if the employer side of this doesn’t pay attention, not only are you losing a ton of productivity in the workplace but you have to deal with turnover, which creates additional expense. The firms and the companies that are out in front of this are going to be so much better off in the long run because they are going to recover better and faster. Their people are going to feel appreciated and valued more. What I’m saying is that it all comes down to culture.

Does your culture value you individually? Does your workplace culture value your contribution to the overall firm or business? We are seeing this whole mass exodus in the employment world. It takes a systemic event like this to make us change. I know it has in terms of law practice. We see the effects on a much broader scale in society.

Thanks for coming and talking to us about burnout. Jody and I pay attention. We try to be in tune with and educate to the extent we can with our readers because we are all people. We need to stay in touch with that side of ourselves or we are going to be doing something else for a job because we are not going to be practicing law if we are not careful.

To your point, there is power in acknowledging a population shock. Unfortunately, we are going to continue to see the effects of this for many years as they bubble to the surface. The more we can talk about it earlier, the better.

One of the things I say is that, “Let’s get back to the way things were,” is the wrong mindset. We can’t move backward, and society has changed. Shift your thinking to, “How we can move forward the best way we can.” Instead of thinking about getting back, think about moving forward. That is a big mindset shift if you start to think about it for a practical level.

You don’t go back and go around. Sometimes you have to go through. That seems like that’s where we are.

Where are we in several years? Part of it is that we don’t know. Learning to accept the unknown is part of the reason we are changed. We don’t know if the school will get canceled next week and if someone will be out with a COVID-19 infection or there will be a judge substitution because of the same reason. There is a lot of unpredictability, which is another reason for stress.

In many ways, if we can work through that stress then we can build an amazing amount of resiliency because we have become accustomed to it. One way to move forward is to become accustomed to our strength in accepting the unknown, shifting gears, and working on the fly. I would love to have that skill. That’s my burnout rant. I appreciate you letting me go on that.

We want to give you the forum to talk about that. That’s something that our profession and readers need to read and feel validated about. From a leadership perspective in a law firm organization, you suggested this. This is an area where it’s okay to be a little vulnerable with your people because that’s what it’s going to take for us to go through this instead of round, over or backward.

The connections that you make in the workplace, coming from a leadership perspective, will strengthen the culture in a firm or in an office where you’ve got leadership that’s willing to put themselves out there on a level like this. You don’t have to lay your whole soul bare and go over your own mental health history and be that forthright about everything. You have to be careful with the “I know how you feel” language.

Even something as simple as listening is a lost art. I hope people are getting back to that now because it’s crucial for where we are. It’s a topic I care about but thank you for that. We are at the end of the time that we had planned to spend together, Katie. One thing that we like to do is ask our guests for a tip or a war story to cap off the discussion. Did you have something that you would like to visit with us about?

I have both in one. My judge required his clerks to take the bar exam. Some people put it off until after their clerkship. I had to take it. As you recall, I had to fill out that character and fitness form and cry to my mental health provider to write the mental health record. It was a disaster. All spring, I was freaking out about it.

By the time it came to take the BARBRI, I was depressed. That’s all there is to it. I was detached. I could not get my brain into it at all. I don’t know why I thought I would pass the bar exam. In the end, I did not pass the bar exam the first time I took it. I missed by less than 1%, which was great. I was like, “My God.” It was out of 350 points, and I had 348. I had that score, and I have to go tell a Federal judge that his clerk has failed the bar exam. I was terrified. I walked into his office with his giant desk, he sat behind it, and I was like, “I failed the bar.” I showed him my thing, and he saw that I only failed by less than 1%. I was ready for him to be angry at me. He had the opposite reaction. He’s like, “This is preposterous.”

He reaches for his phone, and he’s like, “I’m going to call.” He starts rattling off names on the board of examiners for the State of North Carolina. I was like, “Don’t do that. Stop.” He’s like, “I will straighten this problem out.” I’m like, “Don’t do it. I will pass it next time. Thank you, but no.” It felt very loving. He was so open arms that I had failed the bar exam instead of blaming me like, “This has to be a mistake.” It wasn’t that. It was not a mistake. I did fail the bar. One of the things that compelled me to work on the character and fitness stuff later was the line and connection between that failure on the bar exam and being blindsided by the character and fitness. It’s a direct correlation there.

The next year when I knew what was coming and had all the paperwork in order, I filed it and took a BARBRI. I was all peppy about it and played tennis every day to stay in shape. I was super positive and passed with flying colors. The tip is to know about the character and fitness stuff if you are a law student. If you are someone who is in the position to help a law student, make sure they know to check what their jurisdiction’s rules are for mental health.

If they require disclosure, do not let them be blindsided by this. It was not okay to find this out as a 3L in the spring of my 3L year. It took me a year to get over it. I was at the top of my class, I was at a Federal clerkship, and then I failed a bar. My law school was like, “What’s going on with you?” They keep track of these bar passage stats. They wanted to talk to me about why.

A professor went with me to look at my scores like, “What happened?” I couldn’t articulate it at the time but by the next year, in retrospect, my mental health was in an entirely different place. It was because, by then, I was like, “I deserve to be a member of the State Bar of North Carolina,” but a year before, I did not feel that way. Tell the judge that you failed the bar and it did not come out the way I thought it would. I was happy about that. The tip is to look out for law students.

Thanks for telling that story because I know there are folks out there who need that encouragement on a number of levels. Katie, thanks for spending the time with us. We enjoyed having you.

It’s so nice to meet you, Todd, and Jody always nice to speak with you. I appreciate the time to talk about things that I feel passionate about. Thanks.

Important Links

- Katie Pryal

- Gordon & Rees Scully Mansukhani

- Barry Law Review

- Biennial Conference of the Legal Writing Institute

- The Complete Legal Writer

- The Genre Discovery Approach: Preparing Law Students To Write Any Legal Document – Article

- The Complete Bar Writer

- Life Of The mind Interrupted: Essays On Mental Health and Disability in Higher Education

- The Worst Part of the Bar Exam – Article

- Darkness Visible

- Sophie’s Choice

- The Lancet – Article

- State Bar of North Carolina

- https://www.Twitter.com/krgpryal

- https://www.Linkedin.com/in/krgpryal

- https://www.Facebook.com/katieroseguestpryal

About Katie Rose Guest Pryal

Katie Rose Guest Pryal, J.D., Ph.D., is a lawyer and rhetorician—an expert in public discourse and how it influences policy—whose main focus is mental illness and neurodiversity and making the world more accessible to all people. She is also autistic and has bipolar disorder, and she writes and speaks about her experiences living with a neurodivergent mind. She is also an expert in gender-based violence and higher education.

She is the author of the #1 Amazon bestseller Life of the Mind Interrupted: Essays on Mental Health and Disability in Higher Education (2017); the INDIE-Gold-winning The Freelance Academic: Transform Your Creative Life and Career (2019); and the IPPY-Gold-winning Even If You’re Broken: Essays on Sexual Assault and #MeToo (2019). She is also the author of four novels and five legal textbooks. She writes frequently for national publications.

She is an Adjunct Professor of Law at the University of North Carolina School of Law, where she spent 10 years as full-time faculty, and an Instructor in the Drexel University MFA in Fiction program. As a keynote speaker, she is represented by the BrightSight group. She also holds a position as Attorney of Counsel at Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani, LLP.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

A special thanks to our sponsors:

Join the Texas Appellate Law Podcast Community today: